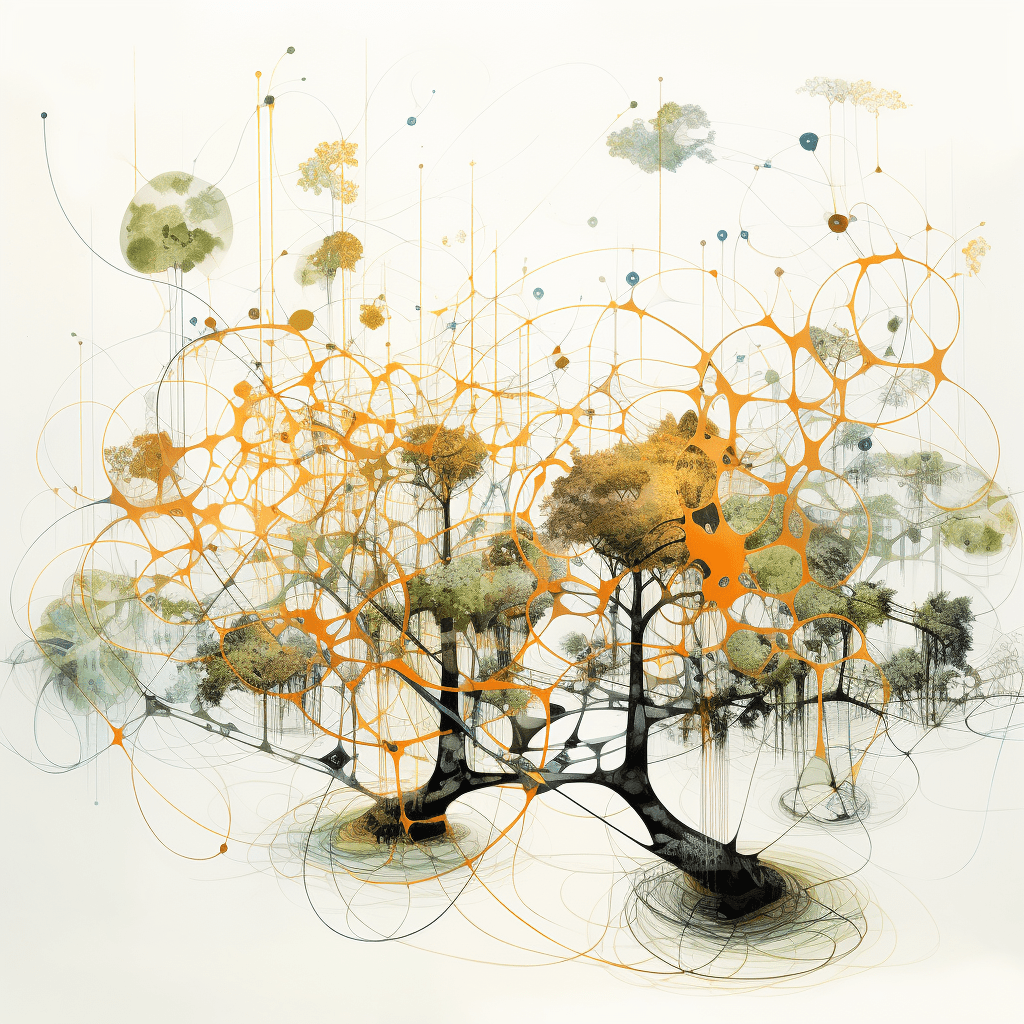

In the rapidly evolving landscape of learning network design, there’s a critical need to construct networks that are at the same time resilient and adaptable, equitable and accessible, authentically engage the human and more-than-human, and are capable of handling increasingly complex challenges. One response might be the speculative concept of the hybrid ecological network — a living synthesis of principles from material ecology, movement ecology and corridor ecology that allows a reimagining of distributed network design.

Material Ecology: Reimagining Nodes

Neri Oxman’s pioneering work in material ecology offers a robust framework for conceptualizing nodes within networks. Each node, akin to a unique material entity in Oxman’s schema, possesses inherent characteristics that enable complex interactions and gives each node a unique material identity (material ontology) that reflects a symbiosis between the human and more-than-human worlds.

Material ecology integrates design and computational biology with traditional fabrication and building processes. It emphasizes the idea that materials are not simply passive substances used to build objects; they participate in the ecological systems in which they’re situated.

If we apply this framework to network design, nodes in the network can be viewed as material entities with their own unique attributes, capabilities, and contexts. Nodes are no longer merely points of connection; instead, they’re akin to unique material entities possessing distinctive characteristics that influence their interactions and behaviour within a network.

In a speculative hybrid ecological network, ‘material’ characteristics could manifest in multiple ways — a node’s ability to process and generate information (its computational capacity), its connectivity to other nodes (its position within the network), or even its resilience in the face of network disruption.

These characteristics aren’t static — just like in Oxman’s articulation of material ecology, they’re continually shaped by their interaction with/in the network environment. A node might develop new ‘material’ characteristics (such as enhanced computational capacity) or lose others (like connectivity) based on its interaction with the rest of the network. This dynamism gives each node a unique material identity or ontology, reflecting the symbiotic relationship between nodes and their network environment.

This perspective enables a more nuanced understanding of networks. By acknowledging the inherent variability and dynamism of nodes, we can design more flexible, resilient networks that can adapt to changing circumstances—much like a natural ecosystem. This outlook resonates with the ethos of material ecology, where the synergy between design, materials, and environment leads to innovative and regenerative solutions.

Movement Ecology: (Re)envisioning Network Flows

Thomas Nail’s exploration of movement ecology provides significant insights into understanding network flows. His theoretical perspective portrays information and ideas as migratory entities, subsequently reshaping the way we perceive the traversal of knowledge and ideas within networks.

Nail postulates that society is essentially constituted by movement, with entities (be they people, objects, or ideas) constantly in flux.

Applying Nail’s philosophy to network design, we can reframe the way we conceptualize the flow of information and ideas within networks. Rather than viewing data as static entities being transferred from point A to point B, Nail’s theories encourage us to see information and ideas as migratory entities.

In this paradigm, information (experience, knowledge, skills) moves, evolves, and interacts with the nodes it encounters, akin to how creatures migrate and interact with their environment in natural ecologies. Just as migratory patterns in nature aren’t purely linear but are influenced by various environmental factors and the organisms’ own agency, the traversal of knowledge and ideas within networks isn’t merely dictated by the network structure but is also influenced by the ‘behaviour’ of the information itself and the nodes with which it interacts.

For instance, some pieces of information might ‘migrate’ quickly across the network due to their relevance or urgency, while others might move slowly or even become ‘dormant.’ The nodes that this information encounters can be seen as ‘habitats’ (see corridors, below) that may alter the information, hold onto it temporarily, or help it evolve or develop further.

This dynamic view of network flows allows for a richer understanding of networks. By acknowledging the agency of information (leading to the potential autonomy of data objects) and the impact of nodes on its movement, we can create networks that are more adaptable and effective in facilitating the migration of knowledge and ideas. This conceptualization of networks as motion interweaves with the hybrid ecology view of networks as vibrant, living ecosystems.

Corridor Ecology: Pathways in Networks

Corridor ecology, an interdisciplinary field including biodiversity corridors and landscape linkages, lends principles crucial to designing pathways within networks. The proposed ‘corridors’ enhance inter-node connectivity and encourage diversity, mirroring the facilitation of movement and genetic diversity through biological corridors in nature.

Seeing network pathways as analogous to biodiversity corridors can open our perception of them as dynamic conduits that facilitate the flow of information and interactions, similar to how ecological corridors facilitate species movement. They are not just passive infrastructure but active and vital parts of the network that can adapt and evolve to better serve the network’s needs.

Ecological corridors are essential for connecting fragmented habitats, allowing species to move and interact — often over multiple generations — thereby enhancing biodiversity, resilience and integration with the surrounding environment. Similarly, in a network context, these ‘corridors’ or pathways can connect different nodes — individuals, groups or systems — and allow for steady, organic evolution of connections between nodes that might otherwise remain siloed from one another. They invite the transfer, mixing, and evolution of ideas and knowledge and foster intellectual diversity and innovation.

By designing pathways that facilitate diverse interactions, we can create networks that are not only more cohesive but also more resilient. These networks can better withstand shocks (such as the loss of a node or disruption to network connections) and are more adaptable, capable of evolving based on the needs of their nodes and the environment.

In addition, the concept of corridor ecology introduces the idea of ‘permeability,’ which refers to how conducive a landscape is to species movement. In network design, this would translate to how easily information and ideas can flow through the network. Designing a learning network with high permeability would mean creating pathways that enable the smooth and efficient flow of knowledge and ideas.

By integrating corridor ecology principles, we can transition from a perception of networks as static, rigid structures to an understanding of them as dynamic, adaptable, and resilient systems, much like ecological landscapes themselves.

Computational Gradients

Computational gradients, representing the dynamic spectrum of data processing and learning capabilities, are incorporated into network design. Nodes adapt and evolve flexibly based on their interactions with the environment and other nodes, reinforcing the network’s dynamism. Gradients can represent the varied capacity of different nodes in the network (individuals, institutions, and technologies) to process, generate, and leverage knowledge and information. Some nodes, equipped with a deeper or richer constellation of resources or positioned advantageously within the network, might be situated on a ‘high’ gradient, processing, creating connections and sharing knowledge at a higher rate.

Conversely, nodes on a ‘low’ gradient might have limited access to information or the means to process it effectively. In a rapidly evolving digital society, the position on this gradient is not fixed; nodes can move along it, driven by technological advancements, education, and societal changes. In the context of a hybrid ecological network, capacities are not uniformly distributed but varied across a spectrum or gradient in a network, influenced by multiple social, economic, and technological factors.

Receptive Learning Networks

Incorporating the principles of receptive learning, nodes in the network transition from passive receivers to active learners, which draws from Bruno Latour’s ideas that networks are both constituted by and constitute their components, making them receptive as they respond to the characteristics and behaviours of their components. and other network theorists. This perspective introduces a radical openness wherein nodes absorb, process, and respond to new knowledge, thereby fostering a dynamic learning environment.

Traditionally, networks are seen as conduits for the transfer of information from one node (or point) to another. A receptive learning network proposes a significant shift in this paradigm. Drawing from the principles of receptive learning, nodes within the network are reimagined not as passive receivers but as active learners (akin to material, movement, and corridor ecologies). This shift is transformative, positioning each node as an active participant in the network, contributing to and shaping the information that flows within it. Each node actively contributes to the network, and the ‘shape’ or state of the network is continuously evolving based on the actions and interactions of its nodes.

Receptive learning, in essence, emphasizes the importance of active engagement and receptivity to new knowledge. In the context of networks, this translates to nodes that are capable of not just receiving but absorbing, processing, and responding to new information. This could mean refining or transforming the information based on the node’s unique context or generating completely new information as a result of learning processes.

In the context of a hybrid ecological network, each node—whether an individual, an organization, or an AI system—is continuously learning and adapting. This fosters a dynamic learning environment within the network, allowing it to stay responsive and resilient in the face of new information or changing contexts.

In essence, the network becomes a vibrant, living ecosystem of learning and adaptation, creating a complex, rich, and diverse environment for the generation and flow of knowledge and experience.

Emergence of Hybrid Ecological Networks

The integration of these ecologies invites a radically open framework that yields a speculative approach to network design that engages the complexity, interactivity, and adaptability found in natural ecosystems. This innovative design interweaves the complexities of material ecology, the directed flows of movement ecology, the interconnectedness of corridor ecology, the evolving computational gradients, and the dynamic principles of receptive learning. In this model, each node — whether an individual, an ecosystem, a more-than-human actor, a group, or automated system — actively engages in the learning process. Knowledge transfer thus evolves from a unidirectional process to a continuous cycle of interaction, adaptation, and evolution.

Each node in the network has the capacity itself to become an active participant more than just a passive presence — one capable of engaging with, processing, and responding to new knowledge and new experiences. This dynamicity and adaptability mark a radical departure from traditional, static network designs and open possibilities for the creation of more resilient, adaptable, and effective networks.

Hybrid ecological networks, while theoretical, underscore the potential of new transdisciplinary thinking, demonstrating how insights from diverse fields can converge to innovate upon established paradigms.

Given the escalating complexity of global ecological and social challenges, the demand for more resilient, adaptable, and interconnected learning networks is paramount. While speculative, hybrid ecological networks propose a dynamic revision of network design — one that embraces complexity, cultivates receptiveness, and advocates for continuous adaptation and learning. This transdisciplinary approach insists upon reimagining traditional boundaries, fostering dialogue and collaboration across different areas of expertise and highlighting the potential for innovation.