Maybe it was the autumn foliage on the verge of turning along the riverbanks and edges of New Hampshire fields, themselves having turned into palettes of ochre and sepia from weeks of late-summer drought — perhaps it was the deepening topography as I drove further north — or likely also it was the late afternoon sun reflecting off the rippling surface of the Pemigewasset River, wider here north of Plymouth, as it makes its way from sources in the White Mountains miles to the north. Whatever the reason, the slightest seed of a Robert Frost poem, like a brilliant white tuft of milkweed on a gossamer wind, made its way into my consciousness. The one line ‘and we lose all manner of pace and fixity in our joys and acquire a listening air’, from his poem ‘The Sound of Trees’ started as a kernel and grew layer by layer to my remembering the whole of the poem by week’s end.

My talk at the Museum of the White Mountains, titled ‘Interwoven Ecologies: Movement and Regeneration in a More-than-Human World’ had Frost’s concept at its very heart — that at our core we are an ‘expression of forces’ of both human and more-than-human worlds, a recognition of a de-centering that can dramatically empower us to engage in the questions of relationality, agency, and more.

In his context, Frost limned a relationship with trees as sentient and relational beings and brought readers into a receptive mode while acknowledging the movement-centered existence that the trees, while perhaps outwardly sedentary, expressed both to and through us — as co-inhabitants of the poem and the transformative power of human/more-than-human relationality.

Frost’s poem stayed with me as I shared the second part of the week at the Garrison Institute in New York’s Hudson River Valley with a wonderful group of approximately sixty leaders from all over the world in conscious food systems, planetary health, regenerative learning, agriculture, consciousness studies, funding, global networking, climate change activism, indigenous ways of knowing, and more — from academia, yes, but largely from practitioners and the non-profit and advocacy sector — to explore how the implementation of consciousness and regenerative practices can help transform food systems at scale.

The questions that surfaced & ideas we shared in our three days at Garrison resonated with my reading of Frost’s poem earlier in the week, and his words kept creeping into the margins of my notes as we shared initiatives on regenerative practice as a ‘process of rebuilding and renewal of the common ground from crisis and collapse to regeneration and renewal’ (Hannah) in the hope that we can reshape and ‘affect value changes and lead to deeper conscious change’ (Andrew) in a reimagination of a range of practices, including an educational framework inviting learners and communities of practice to counter a prevailing exploitative growth-minded outlook and ultimately asking, ‘why are the questions what they are? — and why are the research methodologies shaped the way they are?’ (Nicole)

There were so many layered conversations that engaged with/in the full spaciousness of the former Capuchin Monastery on the banks of the Hudson that it may take months to see how some of the newly spun threads of inquiry will find one another to weave into a more conscious and holistic future for both food systems and broader regenerativeness into which I hope we can see them evolve. Despite the fertility and depth of conversation, and the spaciousness and time, there was an underlying urgency as we sought to find the leverage points where these seeds of radical growth could find fertile soil in which to flourish.

At the same time, I was reading Marica Bjornerud’s wonderful Timefulness, which, with a deep understanding of geomorphology in the context of a contemporary worldview that ‘represents an “epistemic rupture so radical that nothing of the past survives”‘ (161). To help us unmoor from the ‘Island of now’ and destabilize our fixation on the present, Bjornerud invites us to collectively find a way ‘how to turn rocks into verbs’ (61) in order to recognize our own temporal geopositionality in the context of a prevailing seismodynamic and tectonokinetic fluidity.

Bjornerud’s lithico-philosophical sedimentations couldn’t help but send me to my bookshelf seeking my well worn and now fifteen-years’ old reading of Stones of Aran, to find where Tim Robinson similarly asks, ‘what tense must I use to comprehend memories, memories of memories of what is forgotten, words that once held memories but are now just words?’ (8). Exceptional details of the Aran Islands percolate upwards through the karst landscape to momentarily coalesce in turloughs, ‘letting the island recompose itself as music’ through the fluidity of its seasonal movements — ‘Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione’ forever cast and recast along this unmoored archipelago in the North Atlantic.

Farther west still and even farther north, on ᐅᒥᖕᒪᒃ ᓄᓇ, Umingmak Nuna, Land of the Muskox (also known as Ellesmere Island) in northern Nunavut, Robert Frost’s un-fixity leads me (during my long drive back from the Hudson to Boston for my flight home) to Aritha van Herk’s exercise in un-reading along the shores of Lake Hazen, well above the Arctic Circle at some 81°N. As she seeks to reclaim the eponymous character from her well-worn copy of Anna Karenina to ‘free her from her written self’(119) on the remote island that does not permit ‘such bare-faced superficiality’ (94) ‘within this endless light [where] she resists all earlier reading’ (121). For centuries, the far north has itself been written into the psyche of so many in the south as a fixed imaginary (a place, an idea, a feeling, a place of both possibility and fear), so a critical un-reading of a fiction in the reality of an all-too-often mythologized place seeks (not unproblematically, certainly) to re-situate, re-name, de-colonize fictionalized bodies and terrain. It’s much as Alootook Ipellie underscores in his Arctic Dreams and Nightmares, ‘The Arctic is a world unto its own where events are imagined yet real and true to live, as we experience them unfolding each day’ (xix).

Van Herk takes her tack with the wind flowing through Frost’s trees upon the waters rising and falling in Robinson’s turloughs as she un-reads and re-writes self, text, and terrain in a kind of reclamation—a way of freeing bodies and places from a framework of imposed, static, and ultimately marginalizing static narratives.

This work of unsettling static narratives, then—whether of bodies, language, places, or time—reveals the movement inherent at the heart of both human and more-than-human worlds. A resistance to fixity allows us to see the networks of interconnected movements that define us: wind through the trees, seasonal flux of water across landscapes, words within a narrative and the shifting contours that limn our collective and individual understandings. Much as we engaged in practice and conversation at the Garrison retreat last month, where we explored the intersections of consciousness, transformative food systems, and planetary health, this disruption of imposed frameworks encourages a deeper engagement with complexity and relationality. By un-reading and re-imagining these static frameworks (literary, human, and ecological alike), we open pathways for radical, root-deep transformations.

In embracing this dynamism, we re-inhabit these spaces, liberating not only the land and its stories but also ourselves. We are reminded that regeneration—of ecosystems, food systems, education, and consciousness—requires a willingness to disrupt and reshape what has been fixed, opening new possibilities for agency, interdependence, and renewal. Disrupting fixity is not just an intellectual pursuit, but a lived practice, grounding us in the work of reimagining and regenerating our shared futures.

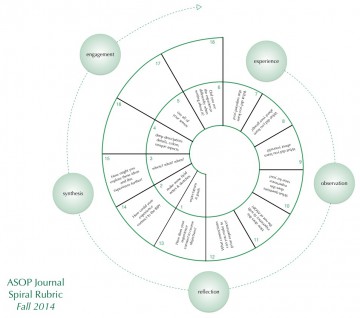

I recently introduced students to the concept of an open rubric, which, for most of them, represented a far more open approach to goal development and self-assessment that they had experienced. The very question, ‘what do you want to learn?’ is enough to catch students off guard, and sometimes requires some processing of what that really means, and that, yes, I’m quite serious that they have to co-design their own learning experience.

I recently introduced students to the concept of an open rubric, which, for most of them, represented a far more open approach to goal development and self-assessment that they had experienced. The very question, ‘what do you want to learn?’ is enough to catch students off guard, and sometimes requires some processing of what that really means, and that, yes, I’m quite serious that they have to co-design their own learning experience.